Rafah is Syrian, and she is tired of war and the pain it brings her family. She used to be a teacher. Now Rafah and her eight children are refugees in Greece.

Her husband, Karim, has got cancer from the chemical weapons used in Syria. Separated from his family, he is being treated in Germany. “The doctors gave him seven to 15 years to live. In camp he would have already been dead,” says Lisa Ament, a Prague-based American volunteer in the Greek port of Piraeus.

“We lost our country, our house, our car. Everything. And this disease will deprive my children of their father. It is a difficult life,” Rafah writes in Farsi in a notebook of Ament; her letter will be later translated to English by another volunteer.

Like many other refugee women, Rafah has to be strong for her children as more of them are fleeing to Europe from the war-torn countries in the Middle East. They dream of a better life in Europe, unaware of conditions that await them there.

The UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) estimates that women and children comprise 52 percent of 247,212 refugees and migrants who arrived in Europe by sea from Jan. 1, 2016 to June. In 2015, 1,015,848 people had arrived of whom 43 percent were women and children, and 57 percent were men.

The men arrived in Europe ahead of their families to find out what the life here is going to be like. Now women and children are only following them, Mary Honeyball, a UK member of the European Parliament, told European Parliament News.

Refugees explain the sudden increase of migrating women and children by a rising fear that the path to Europe will soon be closed completely, reports the Washington Post.

In 2016, 46 percent of the refugees are Syrian and Afghani nationals, according to UNHCR. The vast majority of those risking their lives to cross the European border is stuck in Greek refugee camps with no chance for relocation in the foreseeable future.

Odessa Primus, a volunteer from the Czech Republic who works in Idomeni refugee camp, shared moments of both happiness and despair with the refugees. There she met a Syrian family with five daughters, all under the age of ten, who invited her to their home – a broken-down train compartment.

Primus brought a doll and a small plastic horse for children, later joining them for a family drawing session. It wasn’t flowers and mountains kids pictured, but houses on fire with people dead and war planes in the sky. They also drew a reality of their new lives in the refugee camp. “Waiting in line for food. Those at front smile, while those at the back don’t,” writes Primus on her Facebook blog under the picture of one of the girls holding her drawing. “She says the sun burns them as they wait for food.”

“The detention camps are prisons, closed, cold and without sympathy and humanity,” says Primus.

Morning in the camp starts early – people wake with the sun, trying to get bananas and baby milk from Platanos Refugee Solidarity group. After that, camp-inhabitants either roam around or go to shower. “Shower means: go to the water point, get some in a bucket, and then try and find a bush or something to wash behind,” Primus describes a usual day in the refugee camp.

“Women try and sponge clean themselves in their tents, and wash their kids outside.” During the day they stand in line to get anything: in line for clothes, for the doctor, for diapers, for lunch, for tea, for the phones’ charging station, for dinner, for firewood to keep warm at night, for a tent. Then, late into the evening children and adults sit around the train tracks next to Greece’s border with Macedonia. ‘We are human’ and ‘You cried for Aylan, you cried for Paris, you cried for Brussels, so did we. It’s time to cry for us. We are dying too, just slowly,’ – these are the signs camp-inhabitants hold up when they don’t sing or play cards, Primus says.

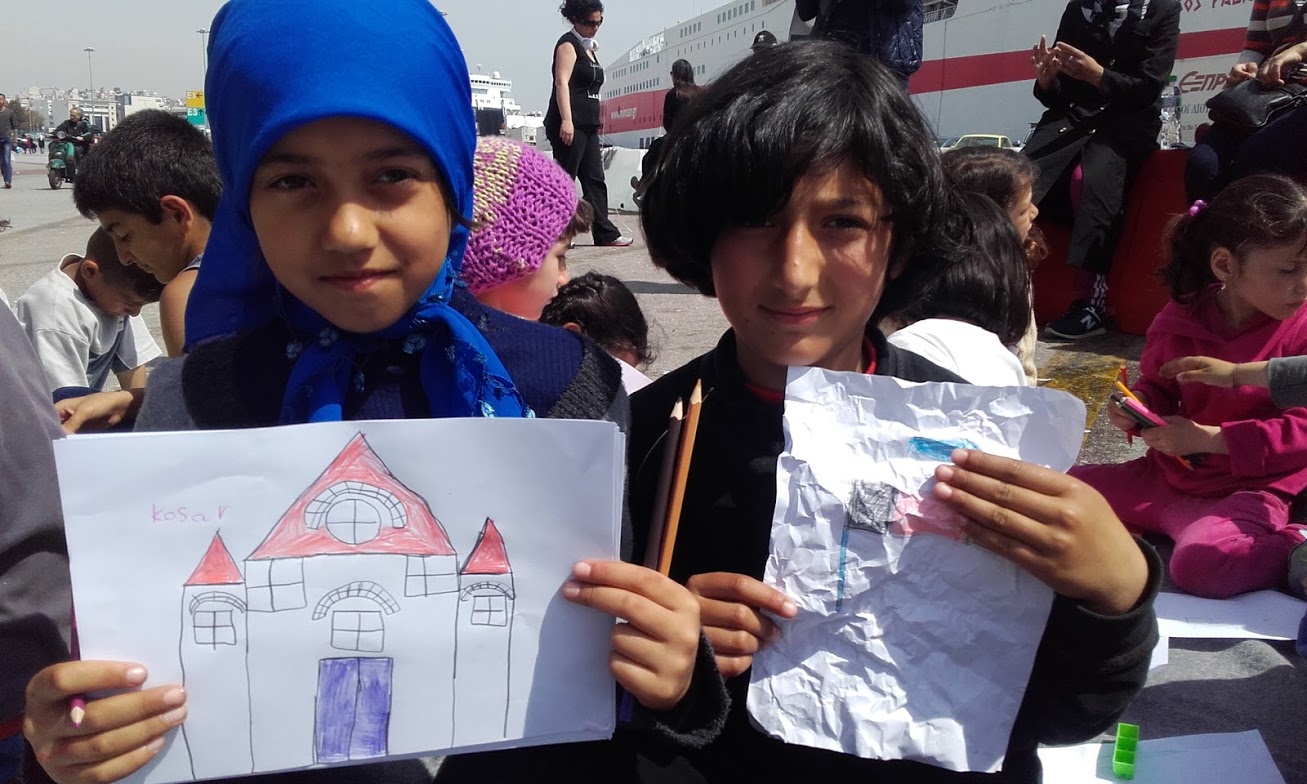

Children in the refugee camps don’t go to school, but they are always eager to play with volunteers. Ament, a preschool teacher in the Czech Republic, helped to arrange a drawing place on the road closed for cars in the Greek port of Piraeus. Some children are so excited to spend two hours with art supplies that they try to steal the markers. “You have to grab their hands and show in sign language – only two, only two,” tells Ament. “But there are 20 hands, so you are trying to lose only half the markers.”

In 2016, 34 percent of the refugees in the camps are children, eight percent more than in 2015, according to UNHCR. There were 10,524 unaccompanied minors reported in 2016. However, the majority of them are still unknown to the officials. “We try and keep an eye out,” Primus says. “But they are too scared to announce themselves from fear of being deported or put in a detention centre.”

Even with parents, children don’t feel safe in Europe.

Primus tells about a family with two boys from the Idomeni refugee camp that wrote her at night asking for a doctor because they were frightened by the effect tear gas had on their children. She was away from Greece, and her medical friends were not allowed in the camp the next day. “The little boys were asking me to send them a voice message, in any language, they just wanted to hear my voice,” Primus writes on her Facebook blog. “They were saying they are scared and miss me.”

Finally, the boys’ mother decided to return to Turkey. Like her, Rafah and thousands other mothers want to find a better life for their children. They don’t know how and where.

“War, sea and even the world – all is against us and there is no place to escape. I’m begging you, presidents! Where is justice? I’m a mother of eight children, and I need someone to support us,” Rafah finishes her letter, adding at the end: “Thank you all.”

Cover photo of Lisa Ament