Che Guevara, or El Che, was a revolutionary whose views on capitalism did not waver. Somehow his image has come to mean different things to each person who dons the pop icon in the form of T-shirts, posters, hats, eating utensils, beach towels, or even alcohol bottles. All for sale, all for the price of participating in a system he despised. The man who accidentally made it all happen was Cuban photographer Alberto Korda.

Well, this is not necessarily true. An Italian businessman, Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, turned radical leftist visited Korda asking for a picture of Guevara and used it as propaganda without mentioning the photographer (however, this did not make the image famous either). Later, Jim Fitzpatrick, an Irish pop artist most known for his rendition of Korda’s image, printed a two-toned image of Che’s portrait after meeting and being enamored by El Che.

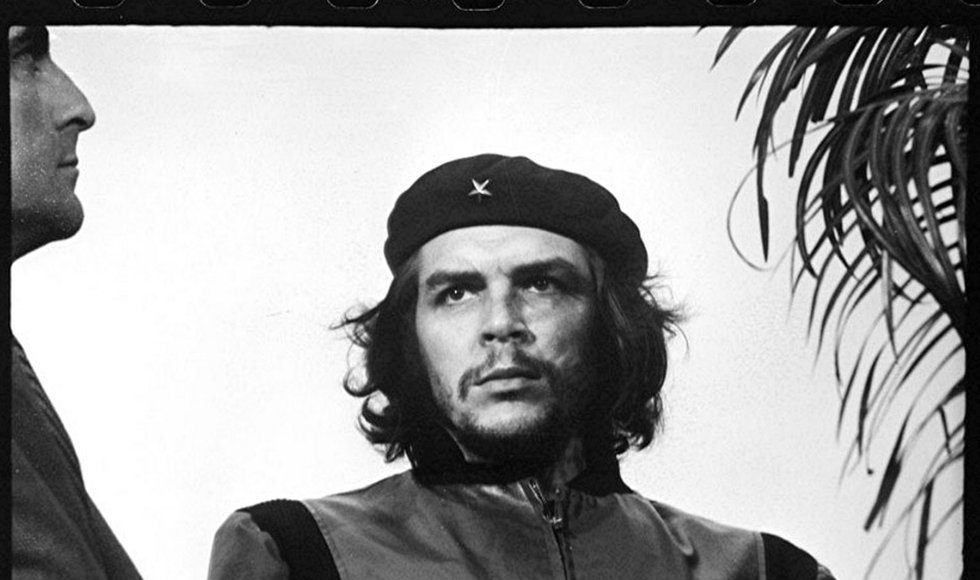

Korda was a fashion photographer, not a documentary photographer. He was not in the habit of taking candid photos, but he believed in the revolution, and every shot he took arose from an interest in what was going on. Ironically, the famous Che image is only a part of the whole. The people who do know that the image originally contained palm fronds to the right and an unknown man to the left, however, are also more likely to know what El Che represents and how he or Korda might have wanted the image to be used.

Although it is highly subjective because neither of the men are alive today, the only people we have left to tell both men’s stories are the close relatives and friends who are the sole protectors of their legacies—legacies that some might think do not deserve protection due to the violence and thousands of deaths that the revolution left in its wake.

Critics see Che as a terrorist and the widespread use of the image as an insult to injury after those dark times in Cuba. This position should not be ignored because the intention of a man is just as important as his actions. It is true that his actions did result in tragedy; that fact should not be ignored. His full story, on the other hand, can be used for good to learn from past mistakes.

Guevara’s charismatic personality is simplified in this famous image, blurring reality. The use of the image as it is today masks the truth. This is what makes it hard for critics to accept because Fitzpatrick’s intention was for his creation to “breed like rabbits.”

The relative running the Korda estate has launched many lawsuits against the capitalistic uses of the Che image. It is claimed that Korda would not have wanted his image to be taken out of context because he looked up to Che and believed in what he was photographing. The Korda estate has tried to capitalize on the image. The photographer never received compensation for the use of his image because he took it under a communist regime when everything fell under the public domain.

Korda was there alongside Guevara; he saw the tragedy, the whole truth, and he chose to stay, to believe. Although Fitzpatrick is responsible for the explosion of the image, he did not fully understand the context and can never understand its brutality. Fitzpatrick is wrong to capitalize on an image he did not take and does not fully understand.

People who buy products with the Fitzpatrick version of the image are usually pawns of a capitalistic society with no power—though producers should be held accountable by consumers for what an image means before it is plastered everywhere.

Now it is as if everyone owns his image, and this is something that Che would have been proud of. Guevara did not believe in capitalism, and he wanted to give back to the people. There is no more powerful, long-lasting way to give back to the people than through a timeless image that has swept the globe as an image of hope, revolution, and power.

The context in which the image is used today varies immensely, with some people not knowing who he was. However, in the Korda estate’s opinion, the use of the portrait that Che would have been most empowered by is in revolution, fighting for a cause for the people. An example of such a movement is the 1968 riot in Paris which led to the pop-art form of Guevara’s image becoming famous. Another is the influence it had on Malcolm X and the Black Panthers: “By any means necessary.”

A transcending meaning is most likely what Che Guevara would have wanted: to have a legacy that has the power to incite revolution and inspire hope at the same time. The meaning will continue to change, for better or for worse. Capitalism has taken its hold, and who knows where it will go next. After all, its diversity is why it became the most used image in history.